Over the next few months, meet four Circle Leaders who have changed their lives with Circles.

“I was doing everything I knew to get out of poverty. But to my shock, it became apparent that I really knew very little about any other economic class other than my own.”

—Rebecca Lewis-Pankratz, McPherson KS

I was raised in poverty, and at age 16, I dropped out of high school and left home with a boyfriend. That began a 13-year period of drugs, alcohol, and an abusive relationship. We moved from Kansas to Texas to Tennessee to Arkansas to Oklahoma.

At age 29, I finally left the boyfriend who was then my husband. Soon after I left, I realized I was pregnant. Thinking of my newborn son and his future, I started college and a job.

I was still struggling with alcohol on and off and with relationships that didn’t last. I had another son and then another. Financial aid helped with tuition, but to make ends meet, I worked as a janitor at my college and as an art instructor for kids. In 2010 when my financial aid ran out, I took a third job as a bartender to cover my final years of tuition.

During that time, I stopped by a church that I frequented to receive free diapers. I told the kind lady who handed out the diapers how much those diapers meant to me and how someday I was going to finish school, claim a better life for my kids, and return to give back. She pointed to a flyer about a class called Circles that helps people get out of poverty.

I thought, “What are these people going to teach me about poverty that I don’t already know?” Then I thought, “I’ve gotten so many diapers from this lady that I better sign up!” So I did.

I was doing everything I knew to get out of poverty. But to my shock, it became apparent that I really knew very little about any other economic class other than my own. I learned I was a master at putting out fires but inept as to how to keep them from igniting.

In 2011, I entered Circles scared, broken, exhausted, and suspicious of the program. But I left that first night with hope and was able to admit how alone and vulnerable I had been all those years.

When I started Circles, my boys were 9, 5, and 2, and we lived in a trailer with broken windows, holes in the floor, and a faulty water heater. I owned a car, but it was always breaking down. I was at work or at school five or six nights each week, which meant dragging my kids home late in the evening from the babysitter. My school-aged kids struggled with behavior issues. And, I felt like a failure as a mother.

Twelve weeks later, I graduated from Circles training. I committed to attend weekly meetings for 18 months. Classmates and I were matched with middle-class “Allies,” who became our friends. Everything in my life started falling into place. My name came up for a housing voucher, and we left the trailer park. A friend helped me find a dependable car. And that year, 2012, I became the first person in my family to graduate from college.

I received a paid, part-time position helping with Circles, and the church that housed our Circles office asked me to be the outreach coordinator for the diaper and food ministry. The first time I went to Walmart and filled up the cart with diapers, I could not stop the tears from streaming down my face. I had become the kind lady who helps moms like me.

I set long-term goals with my Allies. I wanted to get my teeth fixed. Thirteen appointments and $1,700 later, I reached that goal. I wanted out of poverty. In early 2014, I was hired as a full-time Circles coach. I was working three jobs at the time, but with this new position, I was finally making enough to officially leave poverty. My third goal was to buy a home. Looking back, I estimated that I had moved 71 times.

In 2016, I remarried. In 2017, I landed a great job directing student services and poverty issues at a large educational consulting company. Today, my boys are 15, 12, and 9. Our household income is $120,000 per year. And, yes, we own a home. Sometimes I’ll hear a little voice in my head that says, “Rebecca, you’re not poor anymore.” It’s almost unbelievable.

© 2019

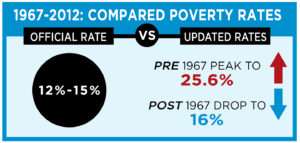

However, unequal inflation rates for necessities such as healthcare and housing have caused census analysts to create updated calculations known as the Supplemental Poverty Measure and Alternative Poverty Measure. Using these more accurate calculations, researchers at Columbia University calculated these new poverty rates from 1967 to 2012 and compared them to the official poverty rates. While the official poverty rate was stable from 12% to 15%, the updated measures showed that the poverty rate was 25.6% prior to 1967 and has dropped to 16% today.

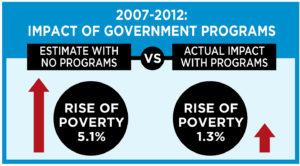

However, unequal inflation rates for necessities such as healthcare and housing have caused census analysts to create updated calculations known as the Supplemental Poverty Measure and Alternative Poverty Measure. Using these more accurate calculations, researchers at Columbia University calculated these new poverty rates from 1967 to 2012 and compared them to the official poverty rates. While the official poverty rate was stable from 12% to 15%, the updated measures showed that the poverty rate was 25.6% prior to 1967 and has dropped to 16% today. Furthermore, researchers compared the updated poverty measures for a five-year time period (2007-2012) with and without government safety-net programs such as U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD); the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC); and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF); and others. Without government programs, poverty rates would have increased 5.1%, but with those programs, poverty rates rose only 1.3%. (For more detailed information, please see the 2016 report by the Office of Human Services Policy, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, titled

Furthermore, researchers compared the updated poverty measures for a five-year time period (2007-2012) with and without government safety-net programs such as U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD); the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC); and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF); and others. Without government programs, poverty rates would have increased 5.1%, but with those programs, poverty rates rose only 1.3%. (For more detailed information, please see the 2016 report by the Office of Human Services Policy, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, titled