Here’s the last of a four-part series focusing on Circle Leaders who have changed their lives with Circles.

“There’s so much support. It’s a ‘push’ support. They want to see you succeed. They want to see you reach your goals.” —DeShawn Daniels, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

I was born and raised in Pittsburgh, the second of four kids. And while we grew up in subsidized housing, I didn’t notice we were living in poverty— my mom never showed the struggle. She always had a job. We had a supportive stepdad who was a constant presence in our lives. And we went on outings as a family. I was practically a teenager before I learned we received food stamps.

I completed high school and the U.S. Army Junior Reserve Officer Training Corps (JROTC). At 19, I received rental assistance, moved out, and started working full-time at a childcare center earning $6.25 per hour. I had a boyfriend and was shocked when he became physically violent. I had never experienced anything like that growing up. Threats from him forced me to move back home.

Still working, I ventured out on my own again at age 24. I got an apartment and a new boyfriend. At age 25, I had a baby girl. When my daughter turned 2, I started college for nursing, but I couldn’t make it work between my job, going to school, studying, and getting her to and from daycare each day. After two semesters, I dropped out but later completed a certified nursing assistant (CNA) program, which helped me get a job at an adult rehab center.

During the next 10 years, I had two sons and continued to work full-time, supporting three kids. I was earning too much money to receive food stamps but was unable to save any money. I had no hope of owning a home until I was invited to a homeownership class, a class that led to Circles.

About five years ago, many families living in the East Liberty neighborhood were displaced and moved into Section 8 housing to make room for a new development. I was one of six people eligible for a program that helps single moms become homeowners. I was in this program when Circles first began in Pittsburgh, and my initial reaction to Circles was no, I didn’t need more meetings. But Circles included childcare and a meal each week, so I agreed to attend.

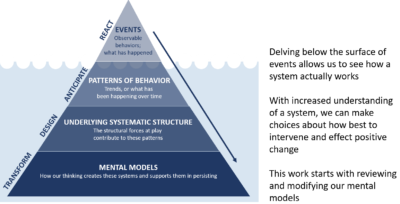

At the first Circles meeting, I wanted to leave because it seemed the others in my class were struggling with issues much worse than mine. I didn’t talk during the first two meetings, but by the third or fourth meeting, I started opening up. Before we met our Allies, we had 12 weeks of training where we shared our stories and learned about all the barriers that keep people in poverty.

We were nervous the day we met our Allies. I thought, “What can they possibly do for me? These people were born into money. How are we supposed to make this work?” Then I realized they were just as nervous as we were.

I discovered my Allies truly cared about me so I kept going back. I was matched with Quianna, who knew all about homeownership because she had just purchased her first home, and Sarah, who is a budgeting queen and knows a lot of people.

The biggest challenge for me was saving money. I was wasting money eating out and buying little, unnecessary things. I didn’t realize it until I wrote it down. They make you write it all down. It was hard to get a paycheck and put the money away. But I was 42 and had no savings. I didn’t have student loans, but I did have some credit card debt. I didn’t know it was hurting me until I saw my credit score.

When the second Circles group started, I stayed. The program got better with each session. I’m now in the fifth class, and Circles is thriving here. Much of the material I know, but I still need all that support. Our Circles has been so much fun we even have a relay team for the Pittsburgh Marathon. I never would have tried this on my own. There’s so much support. It’s a “push” support. They want to see you succeed. They want to see you reach your goals.

At the end of 2018, I purchased a home of my own. My sons’ father is very involved with all three of my kids, who are now 19, 9 and 5. My daughter is a freshman at Seton Hall University. I’m now in charge of scheduling and payroll at the rehab center, and I earn $18.23 per hour. My credit score is 740. I still get excited when I check my credit score every two weeks. It’s a great feeling.

© 2019