When I woke up on January 1, 2050, I joined my large circle of friends to formally celebrate the elimination of poverty from Story County, Iowa. Let me tell you how this happened. It’s an amazing story that few believed possible 60 years ago.

Once we were sure that all our children were safe and healthy, then, and only then, did we turn our attention to making our personal lives more comfortable. Schools no longer charged fees for extracurricular activities. All children now had access to computers in the home so that the playing field was level from the beginning.

We helped couples decide to postpone having children. Adults made the conscious decision to slow down and take the time to really notice the extraordinary individuality of each child in our community. We decided to invest more of our time and energy in raising our children than in the pursuit of wealth. We got so interested in children that we were right there for them, in appropriately sensitive ways, on the very days when they had questions about sexuality, feelings of loss, and anxieties about being loved. We became more sophisticated about what children need from adults and made it our priority to give it to them. We watched while teen births gradually decreased, then became a thing of the past. During 2049 in Story County, no child was born to teenage parents.

Adult parents in Story County learned how to value maintaining a committed relationship above all else—how to simplify life by reducing unnecessary consumption, freeing up time and energy for building and strengthening their commitment. We realized that the benefits of having a successful, lifelong partnership far outweigh the difficulties we all experience sustaining one. People stopped tolerating emotional and physical abuse—indeed, the community developed strong, assertive plans to interrupt patterns of abuse in families.

Men and women realized the necessity of establishing good relationships with one another in order to stay close. People got better about asking friends for help with negotiating the challenges of staying together and raising a family. Children observed these changes and so learned how to choose compatible mates and how to communicate effectively to maintain a good, intimate relationship. The rate of family breakups fell from 50% to 6%.

Employers in Story County saw the wisdom of turning away from short-term earnings, investing more time and money into building teams of steady, reliable, well-paid workers able to fully utilize their talents to provide meaningful services to the community. During the past 40 years, employers have shifted away from generating products and services of questionable value for people and the environment, moving toward a deep commitment to enrich lives, while conserving and renewing natural resources for future generations.

Health insurance became universally accessible, benefiting thousands of vulnerable families in Story County. Many of the county’s older residents still remember the years of preferential medical care; younger people hear those stories with disbelief.

Transportation changed as radically here as in the rest of the nation. Electric vehicles replaced the fleet of polluting cars we once had. Supplementing our clean energy supply by natural gas burning facilities is necessary less than 5% of the time. Electric bus service now extends to all area businesses and communities. The use of bicycles increased dramatically as it became safer and easier to pedal around the county on hundreds of miles of newly constructed bike paths. As generosity and making new friends became a normal way of life, carpooling became easy. People with lower incomes now don’t have to worry about maintaining a car. There are plenty of ways to get where they need to go. Those who absolutely need a car but can’t afford the price can obtain a donated vehicle that has been donated.

The cost of housing decreased dramatically during the past 40 years. No one now has to spend more than 30% of take-home pay for rent. The city of Ames and Story County, through a number of bold public initiatives, paved a clear and reasonable path for anyone to move from affordable, subsidized rental situations to home ownership.

Because adults focused more on children, Story County citizens enthusiastically created the best childcare support system we could. Iowa joined the rest of the states in providing excellent and affordable childcare for all. Most people had more time to spend with their own children because of their commitment to staying together as families, and, as life became more affordable and manageable, they didn’t feel compelled to work ever longer hours.

Story County developed such a powerful social safety network that it became virtually impossible for anyone to suffer poverty in isolation. These emergency financial support services have become just as important to us as our emergency police and fire services. People in our communities now know when families are in financial trouble and so are able to reach out quickly and effectively before evictions, job losses, family breakups, and a host of other destructive outcomes occur. Every community has ample emergency funding, plenty of skilled volunteers and professionals who know how to intervene, and Circles USA to ensure that people don’t fall back into poverty.

A family’s financial crisis is treated as an opportunity for community members to reach out in service to a neighbor—to support a family out of isolation. We have realized that every member of the community has gifts to share, and we’ve stopped wasting human potential by marginalizing individuals and families living in poverty.

When I woke up on January 1, 2050, I realized that at some point during the previous 40 years, a critical mass of people had figured out how to have enough money, enough friendship, and enough meaning in their lives to be truly happy. This core group became the catalyst necessary for making it an eventual reality for all. Story County had been transformed.

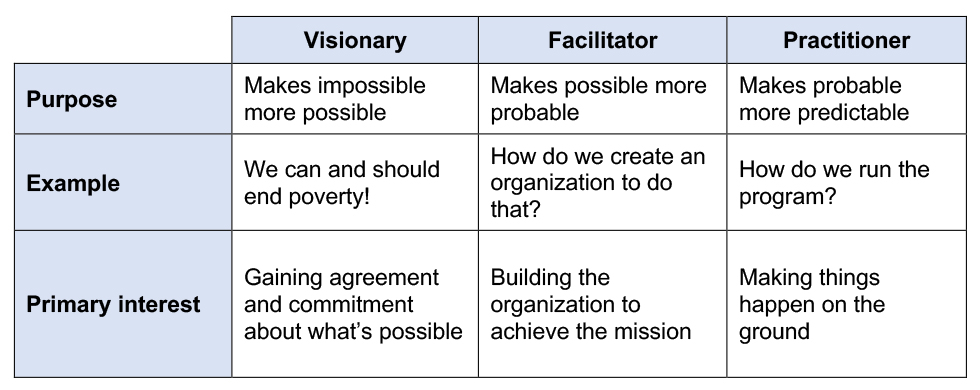

Learn more: Transformational Leadership: A Framework to End Poverty ~ By Scott C. Miller

To learn more about Scott Miller, please see his website here.